Research

Our work focuses on spatial self-organization and pattern formation in ecosystems, using mathematical models, primarily partial differential equations. Here are some themes we currently work on:

Vegetation Spatial Patterns in Global Drylands

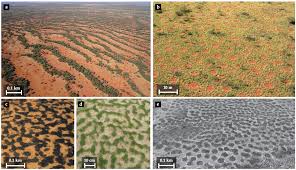

From left to right: (A) self-organized vegetation patterns in dryland ecosystems; (B) a typical reactive-transport model to study Turing pattern formation of dryland vegetation; (C) dryland ecosystems featuring both vascular plants and biological soil crusts.

As environmental change pushes ecosystems toward their limits, there’s a growing need to predict their responses to external pressures. Prior research shows that large-scale spatial patterns in ecosystems can change in predictable ways near tipping points—serving as early warning signs of collapse. Drylands, which are both globally widespread and sensitive, have been a model system for developing this theory.

The prevailing dryland models predict a shift in vegetation patterns with increasing aridity: from gaps in continuous vegetation, to labyrinth-like bands, to spotty patches, and eventually to a bare-soil state. However, such patterns only appear in a small fraction of drylands globally. A likely reason is that current models overlook a crucial ecological component—species interactions, particularly the role of biological soil crusts (biocrusts) in the case of drylands.

To better understand dryland spatial dynamics, we are developing new theories and models that explicitly include biocrust-plant species interactions. Supported by NSF-DEB, our team (co-PIs: Yufang Jin, Rachata Muneepeerakul, Caroline A. Havrilla, and Yu Zhang) aims to build models that explain the broader diversity of vegetation patterns observed in real drylands. See our recent results from the remote sensing analysis and mathematical modeling.

Spatial Self-organization of Benthic Microbial Communities in Antarctic Lakes

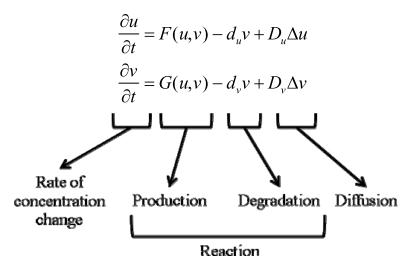

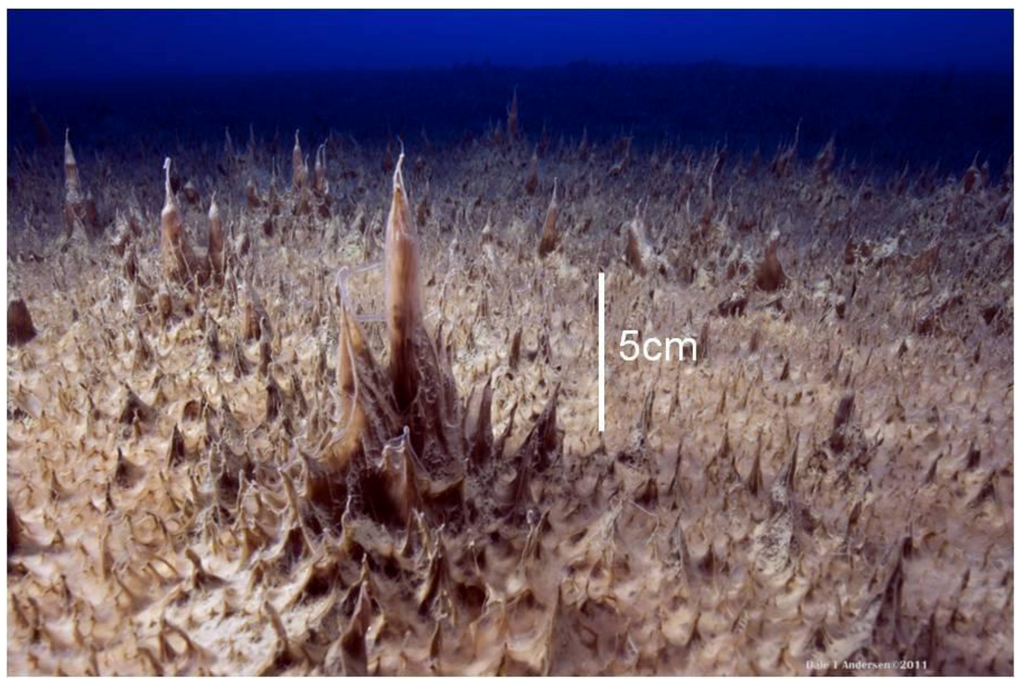

From left to right: (A) microbial communities forming cone structures on the lake floor in Antartic; (B) microbial communities forming pinnacle structure on the lake floor; and (C) cross-section of a pinnacle (read more).

Beneath permanent ice and meters of liquid water in many Antarctic lakes reside structurally complex arrays of spatially self-organized microbial mats, forming pinnacles, cones, or hexagonal structures (modern stromatolites). These unique ecosystems are now being reshaped by global change. We are developing models to predict how environmental changes—particularly the reduction or loss of summer ice cover—might affect, or may have already affected, benthic microbial communities. By integrating the morphology and spatial patterning of these modern stromatolites with their biophysical and biochemical environments, we aim to refine our understanding of the controls on microbial community organization. This, in turn, will improve interpretations of ancient stromatolites in the geologic record and shed light on key questions about Earth’s evolutionary and environmental history.

Collaborating with Dr. Dawn Sumner, we are applying pattern formation theory and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to understand pinnacle-forming microbial mats in Lake Vanda, Antarctica (funded by NSF-OPP) and their response to ice melting under warming.

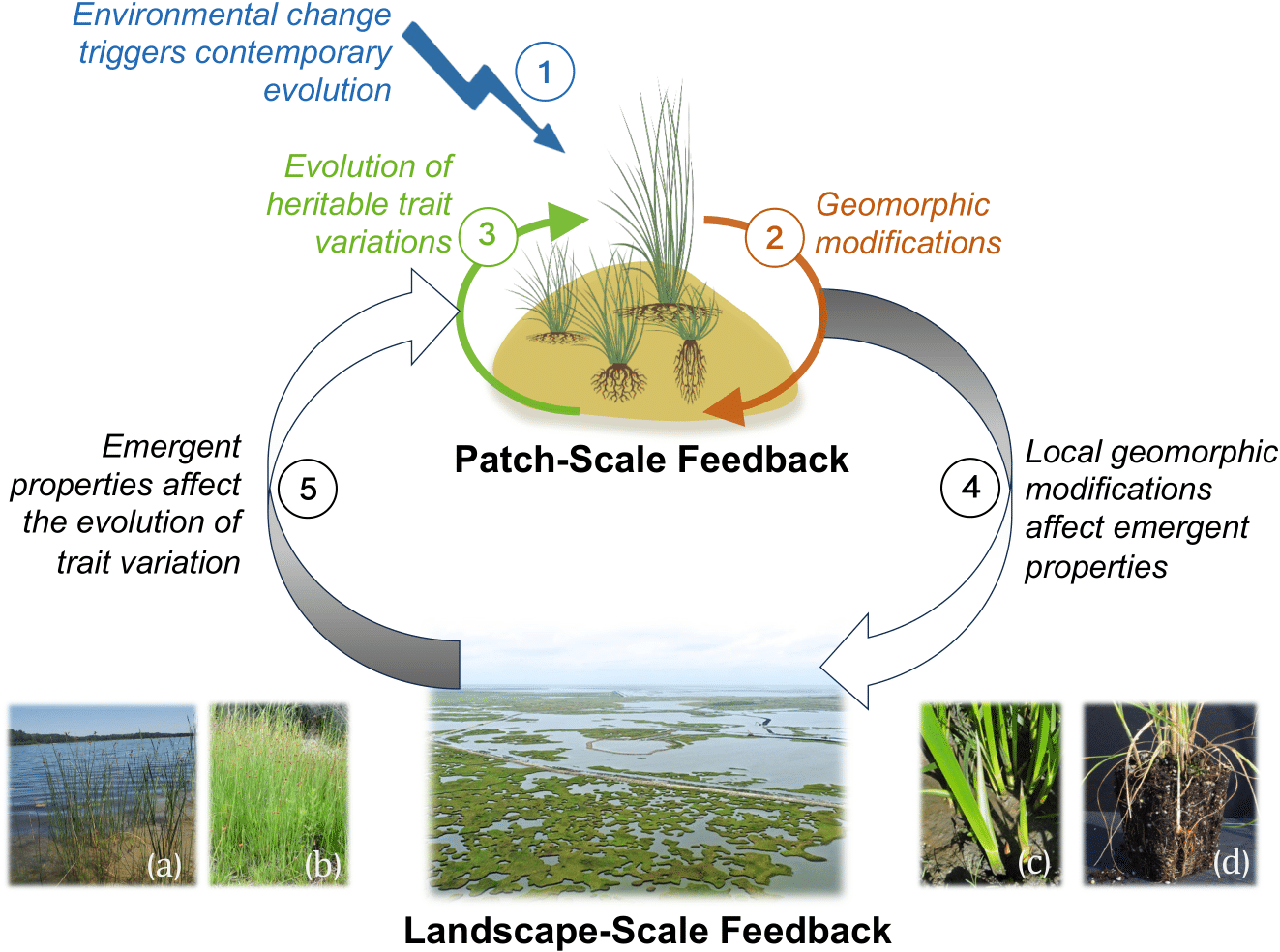

Geo-evolutionary Feedbacks to Couple Evolution of Landscapes and Plants

From left to right: (A) Geo-evolutionary feedbacks using the example of coastal salt marsh landscapes (from Dong et al. 2024); (B) a riverine landscape shaped by vegetation–sediment-flow interactions.

Biological processes affect almost all landscapes on Earth. Their effects are perhaps most prominent in biogeomorphic landscapes such as coastal wetlands, sand dunes, and peatlands. The field of biogeomorphology has been built on observations of the strong influence of organisms on landscapes; however, biogeomorphic models seldom consider genetic or phenotypic changes of organisms, because evolution is perceived to take place slowly and across great distances. Thus, geomorphologists have often assumed that they could safely ignore evolution, especially at fine temporal and spatial scales. However, evidence from evolutionary biology has accumulated that populations can evolve meaningful changes on the same timescales at which they modify the landscape.

Looking at this knowledge gap from the other side, evolutionary biology often does not consider the effect of landscape dynamics on biological evolution. Although the effects of landscape changes on speciation in geological time are relatively well studied, synergistic interactions between evolution and landscape change in contemporary time have not been embodied in evolutionary biology. Such persistent disciplinary barriers have impeded the development of a much-needed integrative theory.

The key realization to our argument is that evolutionary dynamics and landscape change can occur at congruent timescales, thus forming an interplay between the evolution of populations and the dynamics of landscapes on which those populations reside. We are developing new models annd theory that integrate eco-evolutionary and landscape geomorphic dynamics, considering mutual feedbacks between landscape changes and evolution of plants in contemporary times. See this modeling paper and conceptual paper for our most recent results.

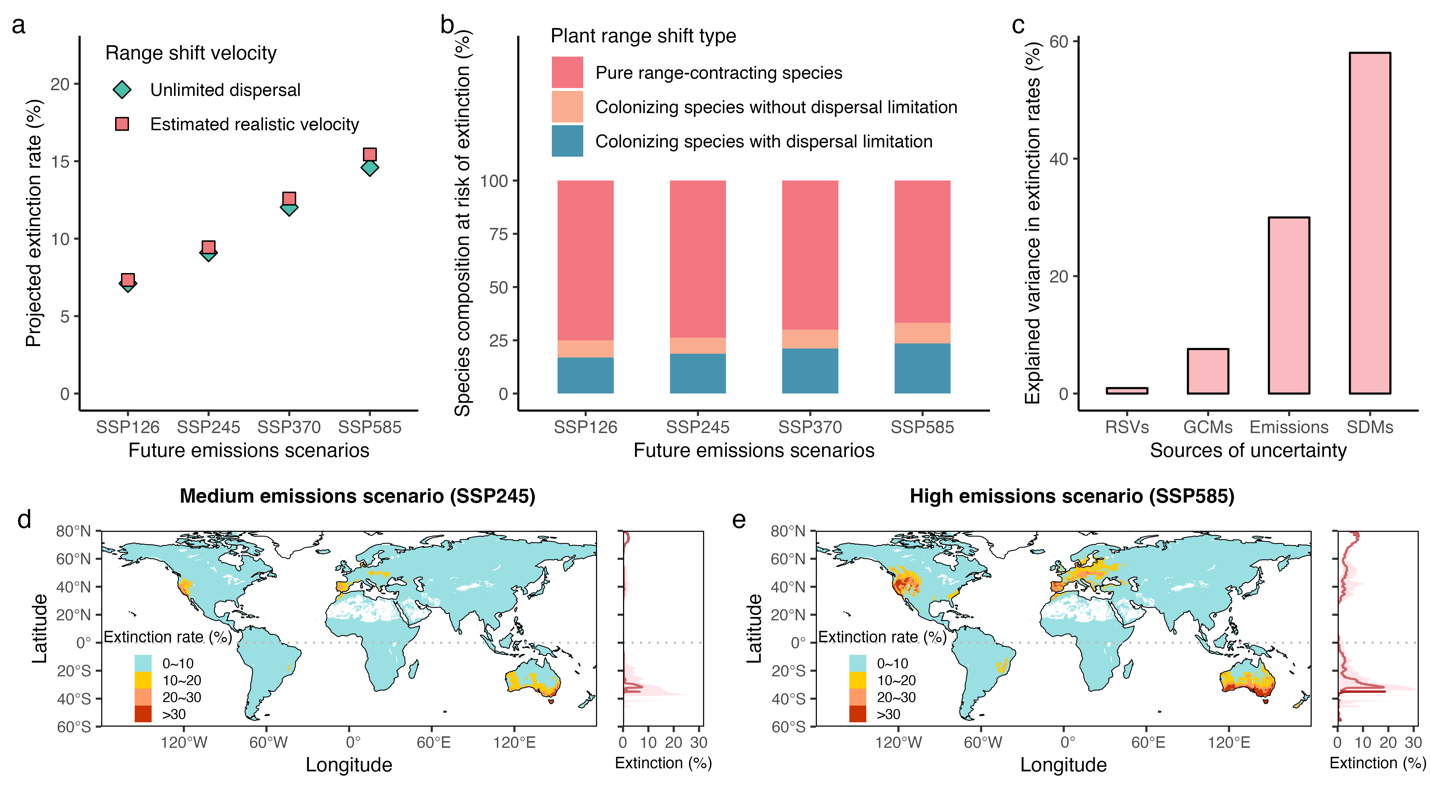

Global Plant Range Shifts under Global Change

Figure above: Causes and global distributions of plant extinction by 2081-2100. (a) Differences in projected plant extinction rates with realistic range shift velocity and unlimited dispersal are negligible. (b) Species at high risk of extinction are dominated by range-contracting plants and colonizing plants not subject to dispersal limitations. (c) Range shift velocity scenarios explained < 1% of variance in projected extinction rates, whereas choice of species distribution models (SDMs) explained most (60%) of the variance. (d) and (e) compares global distribution of plants at high extinction risk under medium (SSP245) and high (SSP585) emissions scenarios (paper under review).

In collaboration with Dr. Francis Moore and Dr. Marc Conte, we are evaluating how climate change reshapes global plant distributions and biodiversity (funded by NSF-DEB).

Using global species distribution models that account for dispersal limitations, local environmental conditions, topographic complexity, and land cover, we investigate the role of plant range shifts in mitigating extinction rates and modifying biodiversity distributions globally. Additionally, we identify regions likely to lose or gain biodiversity, experience novel species assemblages, and host key migration corridors.

We also integrate these ecological outcomes into Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) to better quantify the social cost of carbon. See our results in JUE (2023) and Nature (2023).